Today's excerpt from

The Prisoner List

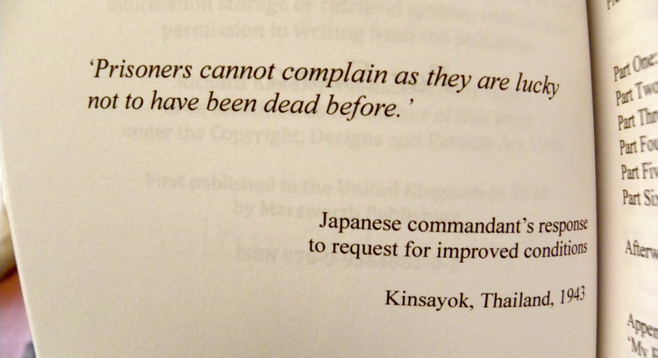

Kinsayok was now a camp of mainly sick and dying men.

The place was in a strange kind of limbo, where little happened and the prevailing mood was one of stunned bewilderment at the barbarity that had just taken place there. In the shadow of the Speedo came delayed shock and the worsening, abject misery of its victims.

The medical officers had their successes, but growing numbers of men were beyond rescue. Some tropical ulcers slowly improved; others continued to rot away at the flesh, leaving no alternative to amputation. Some of the sickest men started to regain their strength and even became fit for light work; others edged closer to death each day. Some clung resolutely to life, determined to return to the way they had been just a few weeks earlier – often in vain; others just lay there, their eyes unfocused, in bleak, hopeless silence.

The Japanese ordered that a large number from the sick huts be transferred back to Tarsao, which had now been designated a hospital camp; others were to be sent to another hospital camp, called Chungkai.

These were not hospitals: just collections of sick huts on a larger scale than those at Kinsayok.

The stretch of track from Kinsayok to the hospital camps had been completed, and so the sick prisoners were to make their journey along the railway that had brought them to this sorry state.

Before they were bundled onto the trucks, the guards forcibly removed the men’s army boots and kept them.

Sick men did not need boots, they said.

The place was in a strange kind of limbo, where little happened and the prevailing mood was one of stunned bewilderment at the barbarity that had just taken place there. In the shadow of the Speedo came delayed shock and the worsening, abject misery of its victims.

The medical officers had their successes, but growing numbers of men were beyond rescue. Some tropical ulcers slowly improved; others continued to rot away at the flesh, leaving no alternative to amputation. Some of the sickest men started to regain their strength and even became fit for light work; others edged closer to death each day. Some clung resolutely to life, determined to return to the way they had been just a few weeks earlier – often in vain; others just lay there, their eyes unfocused, in bleak, hopeless silence.

The Japanese ordered that a large number from the sick huts be transferred back to Tarsao, which had now been designated a hospital camp; others were to be sent to another hospital camp, called Chungkai.

These were not hospitals: just collections of sick huts on a larger scale than those at Kinsayok.

The stretch of track from Kinsayok to the hospital camps had been completed, and so the sick prisoners were to make their journey along the railway that had brought them to this sorry state.

Before they were bundled onto the trucks, the guards forcibly removed the men’s army boots and kept them.

Sick men did not need boots, they said.