Today's excerpt from

The Prisoner List

By early evening, they had reached a place called Tarsao.

The men came off the trucks and were marched down a slippery path into a prisoner-of-war camp. This was not to be their new home: they would be staying here only for the night, and would then move on.

But although their time at Tarsao was to be short, what they saw there as they entered the camp was something that the men would never forget:

‘The very sight of the prisoners at Tarsao horrified us: they were shockingly, dangerously thin.

They wore nothing but loincloths and all their ribs stuck out. They looked to us like walking skeletons.’

The camp consisted largely of makeshift sick huts, erected and held together with bamboo.

Ben and some others went into them. They found in there – as they had feared that they would – friends they had left in Singapore, now desperately ill in this godforsaken place. Some were hardly recognisable.

The friends told them how they had been moved to Thailand months earlier and what had happened to them since. They also mentioned other friends who had travelled with them and who had died from overwork and disease – young men in their twenties, in perfect health when Ben had last seen them fifteen months earlier.

That evening, more than a week after leaving Saigon, the seven hundred travellers finally learned from the skeleton men what was happening.

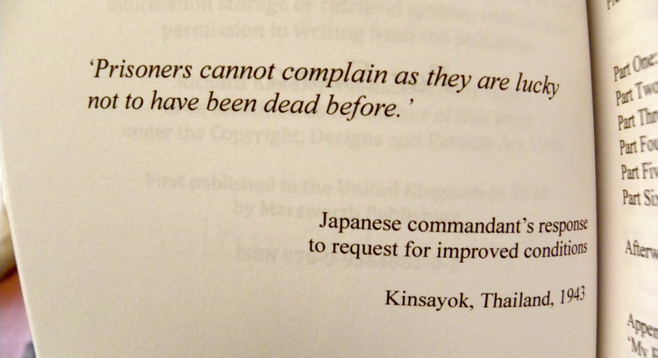

The Japanese were using prisoners of war (and anyone else they could lay their hands on) to build a 260 mile railway from central Thailand into the furthest reaches of Burma. All along the route – through virgin tropical jungle – forced labour camps had been set up for that specific purpose, and new ones were being put up all the time. Tarsao was just one of them.

It was obvious that living and working conditions here had been abominable from the outset. Now, with the start of the monsoon season and the work behind schedule, they had become much worse.

There was not enough food for the seven hundred visitors, and many had nothing to eat.

They trudged across the rain-sodden camp, towards the bamboo huts where they would be spending the night. On their way, they saw a small gathering of half-naked prisoners in the distance. It was a burial service for the railway’s latest victim.

The men came off the trucks and were marched down a slippery path into a prisoner-of-war camp. This was not to be their new home: they would be staying here only for the night, and would then move on.

But although their time at Tarsao was to be short, what they saw there as they entered the camp was something that the men would never forget:

‘The very sight of the prisoners at Tarsao horrified us: they were shockingly, dangerously thin.

They wore nothing but loincloths and all their ribs stuck out. They looked to us like walking skeletons.’

The camp consisted largely of makeshift sick huts, erected and held together with bamboo.

Ben and some others went into them. They found in there – as they had feared that they would – friends they had left in Singapore, now desperately ill in this godforsaken place. Some were hardly recognisable.

The friends told them how they had been moved to Thailand months earlier and what had happened to them since. They also mentioned other friends who had travelled with them and who had died from overwork and disease – young men in their twenties, in perfect health when Ben had last seen them fifteen months earlier.

That evening, more than a week after leaving Saigon, the seven hundred travellers finally learned from the skeleton men what was happening.

The Japanese were using prisoners of war (and anyone else they could lay their hands on) to build a 260 mile railway from central Thailand into the furthest reaches of Burma. All along the route – through virgin tropical jungle – forced labour camps had been set up for that specific purpose, and new ones were being put up all the time. Tarsao was just one of them.

It was obvious that living and working conditions here had been abominable from the outset. Now, with the start of the monsoon season and the work behind schedule, they had become much worse.

There was not enough food for the seven hundred visitors, and many had nothing to eat.

They trudged across the rain-sodden camp, towards the bamboo huts where they would be spending the night. On their way, they saw a small gathering of half-naked prisoners in the distance. It was a burial service for the railway’s latest victim.